Distribution of the Sensorial

- researchpractice

- 2025년 10월 28일

- 4분 분량

최종 수정일: 2025년 11월 11일

Distribution of the Sensorial is an experiment-exhibition that explores accessibility and new media. The show presents results of the Magic Circles virtual worlds’ laboratory by means of non-normative forms of documentation, which seek to engage various senses and activate the audience as a collective body.

With traces of the work of DC Spensley, Debbie Ding, Hortense Boulais-Ifrène, Jan Berger, Gabriel Menotti, and Sojung Bahng

14-17 Oct, 1-6 PM.

18-19 October, 11 AM – 6 PM.

/rosa, 35, Rosa-Luxemburg-Straße, Scheunenviertel, Mitte, Berlin, 10178, Germany

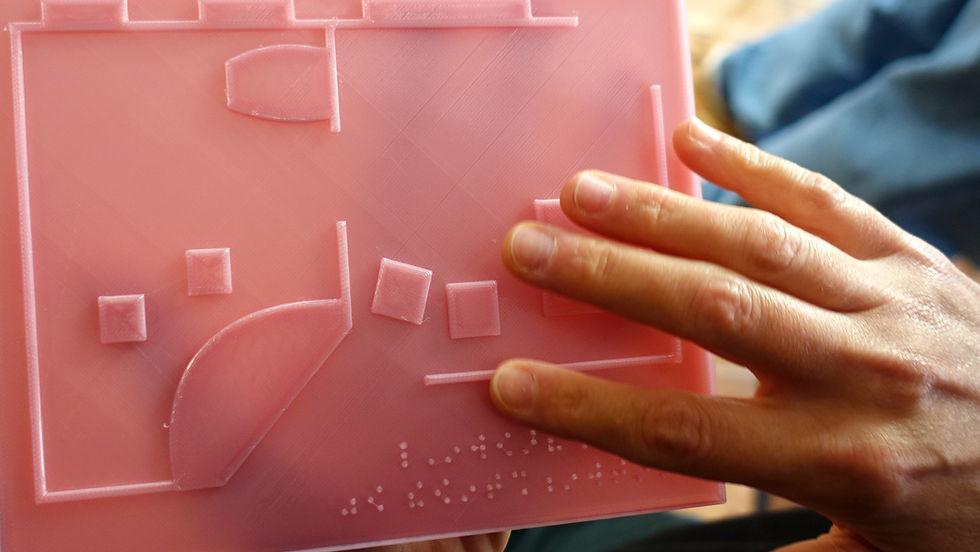

Tactile exhibition layout integrating haptic interfaces and Braille to support spatial perception for visitors with visual impairment.

Tactile portraits of DanCoyote Antonelli (DC Spensley) and the Skydancers Tatiana Kurri, Wythchwhisper, Pielady, and Buffy Beale (Second Life avatars)

Tactile still from the AOC: Movie (Jan Berger)

Pictures of objects from Ouvroir (Chris Marker) with metadata in braille, taken from the inventory made by Hortense Boulais-Ifrène

Walkthrough of The Village with audiodescription by the artist Debbie Ding

Model of a gosiwon created by Sojung Bahng for Wired: Gosiwon.

Models of virtual environments made by Gabriel Menotti for (Old Constellations) Above Vila Itororó.

The exhibition was accompanied by workshops for visitors with visual impairments, organized in collaboration with the Blind Association, and a panel discussion. Further details will be shared.

The excerpt below is from the exhibition's audio guide:

This exhibition is a laboratory. We are experimenting with ways to make new media art more accessible.

You might already know that this has always been difficult. New media art is the kind that relies on technologies that are often expensive and sometimes hard to use. Regular galleries and art professionals don’t know how to operate these devices. Most of the audience don’t know either.

In our case, we are talking about art made for and with virtual worlds. Virtual worlds are online environments that simulate real, tridimensional spaces. People navigate these spaces like they were playing a videogame without any predefined goal. They can be and do almost anything. And some people decide to make artworks: sculptures, performances, sometimes even whole environments.

Last year, we organized a residency called Magic Circles. We gathered five artists from all over the globe working in virtual worlds and, for a little more than a month, visited each other’s spaces. It was a way to learn from each other and experience their creative processes firsthand.

For the whole time, we were thinking about how to best share this learning with a larger crowd. And we always bumped into the same challenges: the equipment required is expensive and not always available; to make it worse, galleries don’t give visitors enough time to get immersed in a virtual world and enjoy its social dimensions. What to do?

We had to accept that the works themselves could not be presented in a gallery. We would have to resort to different forms of documentation: pictures, videos, and descriptions. It’s a common strategy in art. But we thought: since we must produce documentation anyway, why don’t we do it in a way that addresses issues of accessibility more broadly?

In other words, why couldn’t we produce documentation of artworks made for virtual worlds that could be experienced even by people who could not participate in these virtual worlds?

Because that’s another, perhaps larger problem. Virtual worlds are made of image and sound. They reinforce a sensorial hierarchy that cultivates vision above all other forms of perception. This makes virtual worlds really hard to experience, if not impossible, for anyone with vision and auditory impairments.

To make up for it, we decided to resort to a third, often neglected sense: touch. We converted virtual images into physical bas-reliefs and maquettes, making models that could be navigated by hand to provide a sense of spatial composition, organization, and movement. We have also made text in braille and audiodescriptions like this, which provide contextual information about the artworks.

We think of all these elements as interfaces that enable some form of entrance into the virtual reality of the artists’ works. We made these interfaces using digital fabrication technologies like 3D printing. That’s part of our research, and also part of this exhibition’s experiment. We want to devise affordable techniques that any museum and cultural institution can use to increase access to various publics. Can you help us test them?

We invite you to explore this exhibition by feeling your way around it. We are also here to assist. As you will notice, not everything is immediately available. Translating across the senses is a huge task and no interface is perfect. But we think this is another advantage.

We know that the documentation we have made can’t represent any of the artworks in their totality for everyone. The documentation communicates different things to different people. In order to know more, visitors must engage with one another and exchange their impressions.

Perception is a social phenomenon, after all. It becomes fuller and more interesting the more we share it, adding our different perspectives together.

— Gabriel Menotti

Curation: Gabriel Menotti

Production: Paloma Oliveira, Sojung Bahng

Production Assistance: Tamara Sbragio Ganem, Isabella Altoé

Special thanks: Carla Ayukawa; Tereza Havlikova

Distribution of the Sensorial is supported by the Insight Development Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) and the EDII Grant from Connected Minds, in partnership with Zentrum für Netzkunst (ZfN).